Junaid Khan's slow burn

He hasn't burst onto the scene all flamboyance and wild hair, like the stereotypical Pakistani fast bowler, but his bowling has started to talk all right

Osman Samiuddin

08-Jan-2014

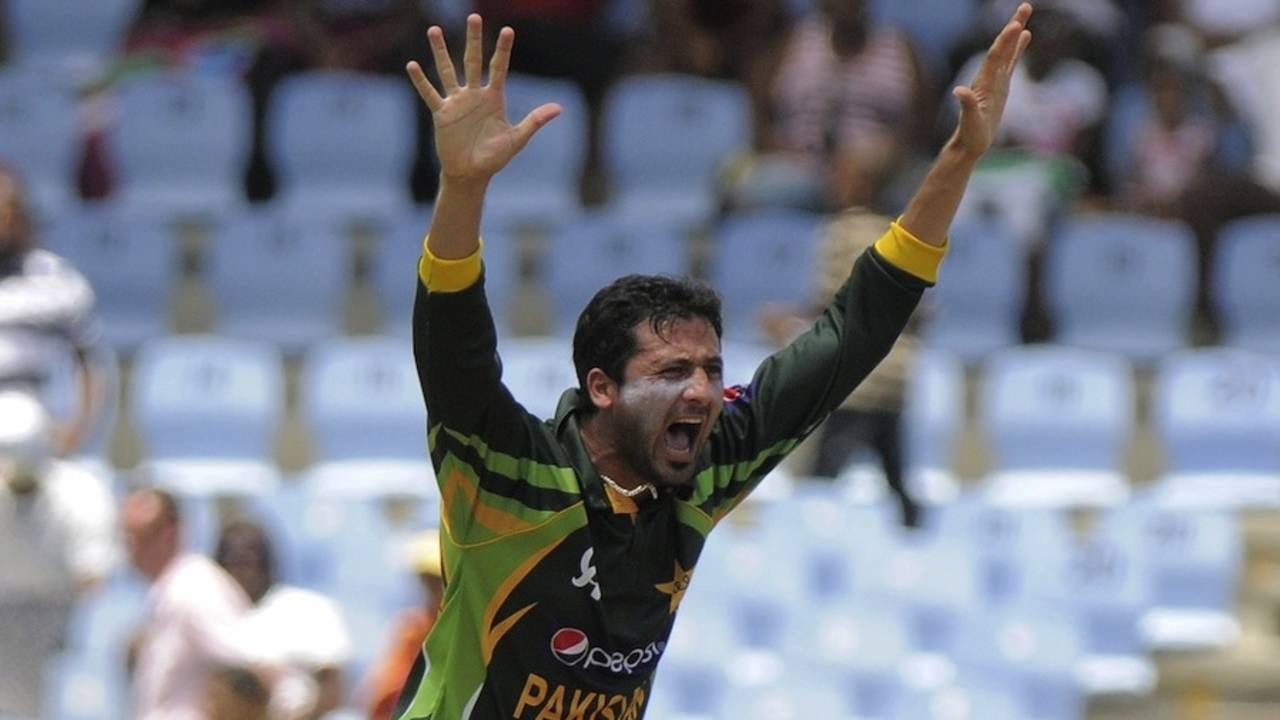

Junaid has made the unfashionable ODI his happy hunting ground • AFP

To cricket journalists, the coach day is a killer. A team has had a stink of a day and nobody wants to make it worse by turning up to explain why. So the coach comes out and tries to make sense of it. It makes for difficult copy. Pakistan has have plenty of coach days too, but they're not so bad because we dread something far worse. We fear most the maa ki dua, jannat ki hawaa player turning up.

Forget the literal translation: a mother's prayers are like the breeze of heaven. It's a popular phrase, found on the back of taxis, trucks and rickshaws. Pakistan's cricket journalists have appropriated it, though, using it as code for a player who will talk in the blandest, most inane way about his performance on the day. "I did well, thanks to my family, my coach, my supporters, blah blah, maa ki dua, jannat ki hawaa." There: make a story out of that. Junaid Khan, bless him, is a part of this breed.

Nearly three years ago, at the 2011 World Cup, Junaid had his first major interaction with big media. It became clear immediately, despite a cute reference to Youtube, that Junaid's words would struggle to make great copy. On the first day of the first Test against Sri Lanka in Abu Dhabi last week, he turned up again to talk about his five-wicket haul in the first innings. He managed to speak about his performance, his career, his progress, his influences, all in less than three minutes - including time for translations. If he had actually said maa ki dua, jannat ki hawaa it might have lasted longer.

Luckily his bowling has become far more eloquent, especially over the last year. Junaid's rise has actually been the real story for Pakistan in 2013. Saeed Ajmal, hair flattened by heavy roller or not, is the main man always; Mohammad Irfan's own rise has been nigh on unbelievable and a wonderful story. Whatever attention remained was consumed by the tragicomedy of Dale Steyn-Mohammad Hafeez and the Camusian debates around Misbah-ul-Haq's captaincy.

In all this noise Junaid has not exactly slinked his way through the year unnoticed. But he's not, let's face it, done it the way we're used to Pakistani fast bowlers doing it. A young Pakistani fast bowler arrives on the scene with the pomp and preening of a groom arriving at his own wedding, atop a white horse, revellers dancing, the band and baaja joyously signalling his entrance. There's no way to miss it. Junaid has been a mere guest at the wedding, a distant relative. His has been a more graded progression, a kind of accumulated momentum over three years coming good now. Actually, it's been a little unnerving in that sense.

This year Junaid has not dropped himself like a bomb on batsmen. That is perhaps not his way, though it has led one former fast bowling grandee to assess - hastily maybe but not entirely outrageously - that he is not an attack leader but a very fine third seamer. Instead he has laid out elaborate minefields for batsmen to walk through, but really, the outlook in coming out unscathed is pretty bleak. Twice in Abu Dhabi, Jacques Kallis couldn't do it. Just recently, in the last ODI at the same venue, Kumar Sangakkara couldn't: he was pulled slowly across to the off side over three overs; Junaid then bowled one straighter, slanting in to bowl an out-of-place Sangakkara round his legs, and these are but a couple of Instragramable snaps from a whole, sparkling album.

There is a chain around his neck, an essential accoutrement for all pedigree fast bowlers. The little tuft of facial hair beneath the lip has not gone unnoticed. The hair is catching up to contemporary fashion

It is in that format that Junaid's bloom has been most fragrant, which maybe explains the lack of gusto in celebrating him: the only thing more unfashionable than an ODI is a specialist wicketkeeper, or an MBA. There has not been a patch of a 50-over innings where Junaid has not thrived. With the new ball he did for India on the cusp of 2013 with one of the spells of the season. With a softer ball, in the dead air that is the ODI middle overs, he showed against Sri Lanka in this latest series the continuing relevance of a fast bowler who seeks wickets. In South Africa he bowled an over of such death the Grim Reaper put down his scythe and applauded. In much more has been evident greater degrees of skill, enhanced game awareness and unflagging stamina, a package requiring only the wrapping and posting.

Round the wicket he is already as comfortable as any current left-armer, though maybe he seeks that comfort too readily. The angle does give his growing range an airing, especially the one that doesn't just straighten but cuts away. The bouncer, among other tools, from that angle is especially deceptive, quicker than expected and almost always honed to harry down the batsman's throat.

High praise comes from the man who has led him through this entire phase, the man who, in the absence of Umar Gul and others, has needed him most. "He is the kind of a bowler we needed," says Misbah-ul-Haq. "We didn't have Gul and Junaid played a leading role, especially at crucial moments for us. In ODIs, in tough situations, during the last overs, at crucial stages in so many matches he has gotten us wickets. In Tests he has been outstanding, not just with the new ball but with the old ball. He's been a really improved bowler."

More than most Misbah is best placed to recognise Junaid's virtues and his measured drift upwards. If ever a man was more than the sum of what he arrived with, who has sweated his way up, it is Misbah. Natural gifts and talent are a ropey area but the impression that Mohammad Amir, to take one relevant example, arrived readier than Junaid does not feel inaccurate. "Yes, there are bowlers who come, and because they have natural attributes like pace and swing they come and have success immediately," says Misbah. "Junaid has improved through his own commitment and hard work. He has done it by going through difficult situations, and his temperament he has shown in crunch situations. When you need someone, at some point to take wickets, you look to someone like Ajmal, but Junaid is also one of those now, as one you can give the ball to and he will respond. He has everything now."

Everything and maybe now even an on-field personality, beyond just that endearing, momentum-gathering hop at the start of his run-up (higher now, for some reason than before). There is a chain around his neck, an essential accoutrement for all pedigree fast bowlers. The little tuft of facial hair beneath the lip has not gone unnoticed. The hair is catching up to contemporary fashion (the faux hawk could happen but longer locks, to add to the effect of the run-up, are always preferable). Those wicket celebrations are a little too uncontrolled and uncoordinated right now, high on adrenalin, low on image-building. What might really help, though, is a big series, in England or Australia. As he pointed out after picking up his fourth five-wicket haul, all against Sri Lanka, the bulk of his Test achievements are against them because half of his 14 Tests have come against them. That, by every comparison, is a fairly low-voltage contest.

During that first Test with Sri Lanka, he reached 50 Test wickets, in 14 Tests. That, nobody will have missed, is the exact number of Tests Amir played, and Junaid has just one wicket fewer. The averages and strike rates don't have much between them, though they couldn't be more apart in the way they were arrived at. Amir, and his absence, will forever remain a deep wound of course. But at least, in Junaid, there is hope of an eventual balm.

Osman Samiuddin is a sportswriter at the National